The study of Hoon can be divided into two parts: syntax and semantics.

The syntax of a programming language is the set of rules that determine what counts as admissible code in that language. It determines which characters may be used in the source, and also how these characters may be assembled to constitute a program. Attempting to run a program that doesn’t follow these rules will result in a syntax error.

The semantics of a programming language concerns the meaning of the various parts of that language’s code.

In this lesson we will give a general overview of Hoon’s syntax. By the end of it, you should be familiar with all the basic elements of Hoon code.

Hoon Characters

Hoon source files are composed almost entirely of the printable ASCII characters. Hoon does not accept any other characters in source files except for UTF-8 in quoted strings. Hard tab characters are illegal; use two spaces instead.

> "You can put ½ in quotes, but not elsewhere!"

"You can put ½ in quotes, but not elsewhere!"

> 'You can put ½ in single quotes, too.'

'You can put ½ in single quotes, too.'

> "Some UTF-8: ἄλφα"

"Some UTF-8: ἄλφα"Reading Hoon Aloud

Hoon code makes heavy use of non-alphanumeric symbols. Reading off code aloud using the proper names of ASCII symbols is tedious, so we’ve mapped syllables to symbols:

ace [1 space] gap [>1 space, nl] pat @

bar | gar > sel [

bas \ hax # ser ]

buc $ hep - sig ~

cab _ kel { soq '

cen % ker } tar *

col : ket ^ tic `

com , lus + tis =

doq " mic ; wut ?

dot . pal ( zap !

fas / pam &

gal < par )Learning and using these names of non-alphanumeric symbols is entirely optional; you can become an expert Hoon programmer without them. Many Hoon programmers find them helpful, however, particularly when talking to someone else who knows them.

Note that the list includes two separate whitespace forms: ace for a single space; gap is either 2+ spaces or a newline. In Hoon, the only whitespace significance is the distinction between ace and gap -- i.e., the distinction between one space and more than one.

Expressions of Hoon

An expression is a combination of characters that the language interprets and evaluates as producing a value. Hoon programs are made up entirely of expressions.

Hoon expressions can be either basic or complex. Basic expressions of Hoon are fundamental, meaning that they can’t be broken down into smaller expressions. Complex expressions are made up of smaller expressions (which are called subexpressions).

There are many categories of Hoon expressions: noun literals, wing expressions, type expressions, and rune expressions. Let’s go over each.

Noun Literals

A noun is either an atom or a cell. An atom is an unsigned integer and a cell is a pair of nouns.

There are literal expressions for each kind of noun. A noun literal is just a notation for representing a fixed noun value.

We start with atom literals. Each of these is a basic expression of Hoon that evaluates to itself. Examples:

> 1

1

> 123

123

> 123.456

123.456

> 'hello'

'hello'

> ~zod

~zodRecall from Lesson 1.2 that even though atoms are unsigned integers, they can be pretty-printed in different ways. The way an atom is to be represented depends on its aura. The literal syntax for each of the hard-coded auras will be explained further in Lesson 2.1.

Cell literals can be written in Hoon using [ ]. Cell literals are complex, because other expressions are put inside the square brackets. Examples:

> [6 7]

[6 7]

> [[12 14] [654 123.456 980]]

[[12 14] 654 123.456 980]

> ['hello' 0xdad]

['hello' 0xdad]

> [123 [~zod ~ten] .1.2837]

[123 [~zod ~ten] .1.2837]You can also put complex expressions inside square brackets to make a cell. These are valid expressions but they aren’t cell literals, naturally:

> [(add 22 33) (mul 22 33)]

[55 726]Wings

A wing expression is a series of limb expressions separated by .. A deeper explanation can be found on the wing and limb reference pages.

Let’s start with the base case: a single limb. A limb expression is a trivial wing expression -- there is only one limb in the series. Some one-limb wings:

+2-+>&4abaddmul

As a special limb we also have $. This is the name of the arm in special one-armed cores called “gates”. (We’ll cover the role of $ in Lesson 1.4.)

Wing expressions with multiple limbs are complex expressions. Examples:

+2.+3.+4-.+.+resolution.path.into.subject+>.$a.b.c-.b.+2-.add

Type Expressions

Hoon is a statically typed language. You’ll learn more about the type system later in the chapter. For now, just know that Hoon’s type system uses special symbols to indicate certain fundamental types: ~ (null), * (noun), @ (atom), ^ (cell), and ? (flag). Each of these symbols can be used as a stand-alone expression of Hoon. In the case of @ there may be a series of letters following it, to indicate an atom aura; e.g., @s, @rs, @tas, and @tD.

They may also be put in brackets to indicate compound types, e.g., [@ ^], [@ud @sb], [[? *] ^]. (Technically these expressions don’t always indicate compound types. In certain contexts they’re interpreted in a different way. We’ll address this variation of meaning in Lesson 2.3.)

Rune Expressions

A rune is just a pair of ASCII characters (a digraph). You’ve already seen some runes in Chapter 1: |=,|%, and |_. We usually pronounce runes by combining their characters’ names, e.g.: “ket-hep” for ^-, “bar-tis” for |=, and “bar-cen” for |%. As stated previously, these names are entirely optional.

Expressions with a rune at the beginning are rune expressions. Most runes are used at the beginning of a complex expression, but there are exceptions. For example, the runes -- and == are used at the end of certain expressions.

Runes are classified by family (with the exceptions of -- and ==). The first of the two symbols indicates the family -- e.g., the ^- rune is in the ^ family of runes, and the |= and |% runes are in the | family. The runes of particular family usually have related meanings. Two simple examples: the runes in the | family are all used to create cores, and the runes in the : family are all used to create cells.

Rune expressions are usually complex, which means they usually have one or more subexpressions. The appropriate syntax varies from rune to rune; after all, they’re used for different purposes. To see the syntax rules for a particular rune, consult the rune reference. Nevertheless, there are some general principles that hold of all rune expressions.

Runes generally do not need to be closed. In other languages you’ll see an abundance of terminators, such as opening and closing parentheses, and this way of doing this is largely absent from Urbit. That’s because all runes take a fixed number of children. Children can themselves be runes (with more children), and Hoon programs work by chaining through these series of children until a value -- not another rune -- is arrived at. This makes Hoon code nice and neat to look at.

Tall and Wide Forms

There are two rune syntax forms: tall and wide. Tall form is usually used for multi-line expressions, and wide form is used for one-line expressions. Most runes can be used in either of tall or wide forms. Tall form expressions may contain wide form subexpressions, but wide form expressions may not contain tall form.

The spacing rules differ in the two forms. In tall form, each rune and subexpression must be separated from the others by a gap -- that is, by two or more spaces, or a line break. In wide form the rune is immediately followed by parentheses ( ), and the various subexpressions inside the parentheses must be separated from the others by an ace -- that is, by a single space.

Seeing an example will help you understand the difference. The :- rune is used to produce a cell. Accordingly, it is followed by two subexpressions: the first defines the head of the cell, and the second defines the tail. Here are three different ways to write a :- expression in tall form:

> :- 11 22

[11 22]

> :- 11

22

[11 22]

> :-

11

22

[11 22]These all do the same thing. The first example shows that, if you want to, you can write tall form code on a single line. Notice that there are two spaces between the :- rune and 11, and also between 11 and 22. This is the minimum spacing necessary between the various parts of a tall form expression -- any fewer will result in a syntax error.

Usually one or more line breaks are used to break up a tall form expression. This is especially useful when the subexpressions are themselves long stretches of code. The same :- expression in wide form is:

> :-(11 22)

[11 22]This is the preferred way to write an expression on a single line. The rune itself is followed by a set of parentheses, and the subexpressions inside are separated by a single space. Any more spacing than that results in a syntax error.

Nearly all rune expressions can be written in either form, but there are exceptions. |% and |_ expressions, for example, can only be written in tall form. (Those are a bit too complicated to fit comfortably on one line anyway.)

Nesting Runes

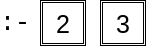

Since runes take a fixed number of children, one can visualize how Hoon expressions are built by thinking of each rune being followed by a series of boxes to be filled -- one for each of its children. Let us illustrate this with the :- rune.

Here we have drawn the :- rune followed by a box for each of its two children. We can fill these boxes with either a value or an additional rune. The following figure corresponds to the Hoon expression :- 2 3.

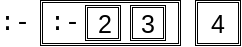

This, of course, evaluates to the cell [2 3]. This next figure corresponds to the Hoon expression :- :- 2 3 4.

This evaluates to [[2 3] 4], and we can think of the second :- as being “nested” inside of the first :-.

What Hoon expression does the following figure correspond to, and what does it evaluate to?

Right. This represents the Hoon expression :- 2 :- 3 4,

and evaluates to [2 [3 4]]. Remember, though, that if you input this into dojo it will print as [2 3 4].

Thinking in terms of these “LEGO block” diagrams, as well as the more literal binary tree diagrams utilized in Lesson 1.2, can be a helpful learning and debugging tactic.

Exercise 1.3a

Draw binary trees corresponding to the above figures. Determine a one-to-one correspondence between linearly ordered nested boxes (i.e. what is depicted in the above figures) and binary trees. You will need to make use of the convention [a [b c]] = [a b c].

Irregular Forms

Some runes are used so frequently that they have irregular counterparts that are easier to write and which mean precisely the same thing. Irregular rune syntax is hence a form of syntactic sugar. All irregular rune syntax is wide. (It follows from this that all tall form expressions are regular.)

Let’s look at another example. The .= rune takes two subexpressions, evaluates them, and tests the results for equality. If they’re equal it produces %.y for “yes”; otherwise %.n for “no”. In tall form:

> .= 22 11

%.n

> .= 22

(add 11 11)

%.yAnd in wide form:

> .=(22 11)

%.n

> .=(22 (add 11 11))

%.yThe irregular form of the .= rune is just =( ):

> =(22 11)

%.n

> =(22 (add 11 11))

%.yThe examples above contain another irregular form: (add 11 11). This is the irregular form of %+, which calls a gate (i.e., a Hoon function) with two arguments for the sample.

> %+ add 11 11

22

> %+(add 11 11)

22The irregular ( ) gate-calling syntax is versatile -- it is also a shortcut for calling a gate with one argument, which is what the %- rune is for:

> (dec 11)

10

> %- dec 11

10

> %-(dec 11)

10The ( ) gate-calling syntax can be used for gates with any number of arguments.

You can find other irregular forms in the irregular expression reference document.

Expressions That Are Only Irregular

There are certain irregular expressions that aren’t syntactic sugar for regular form equivalents -- they’re solely irregular. There isn’t much in general that can be said about these because they’re all different, but we can look at some examples.

Below we use the ` symbol to create a cell whose head is null, ~.

> `12

[~ 12]

> `[[12 14] 16]

[~ [12 14] 16]Putting ,. in front of a wing expression removes a face, if there is one.

> -:[a=[12 14] b=[16 18]]

a=[12 14]

> ,.-:[a=[12 14] b=[16 18]]

[12 14]

> ,.-:[[12 14] b=[16 18]]

[12 14]

> +:[a=[12 14] b=[16 18]]

b=[16 18]

> ,.+:[a=[12 14] b=[16 18]]

[16 18]To see other irregular expressions, check the irregular expression reference document.

The Standard Library

The Hoon standard library is a compilation of generally useful Hoon gates (functions). You’ve seen these already: in expressions like (add 11 11), add is a function from the standard library.

It’s important to know about standard library functions, because they make certain tasks much easier, and spare you from having to write the code itself. If you did not use the add library function, for example, you would have to write out code like this every time you wanted to find the sum of two numbers:

++ add

~/ %add

|= [a=@ b=@]

^- @

?: =(0 a) b

$(a (dec a), b +(b))

Standard library functions are often built with other standard library functions, but ultimately those functions used are only built with runes. Notice how in the code above add is built with the dec function, which decrements a value by 1.

Reference Materials

The Hoon syntax can be intimidating for the uninitiated, so it’s good to remember where you can look up expressions. The Reference section itself is a good place to find the materials that you need. These children sections are likely to be useful:

- The Runes page will show you how to use any Hoon rune.

- The Cheat Sheet is a more compact place to look up rune expressions.

- The Standard Library section has its sub-pages arranged by category. So arithmetic functions, for example, are all found on the same page.

- The Hoon Style Guide will show you how to write your Hoon code so that it’s idiomatic and easily understood by others.

Debugging

When you have an error in your Hoon code, one of two things can happen. Either the code does not run at all and you get an error (such as nest-fail), or your code does run but produces the wrong results. The Troubleshooting page is a good resource for figuring out how to debug your code.

There are a couple useful runes associated with debugging:

!: (zapcol), if written at the top of a Hoon file, turns on a full debugging stack-trace. It’s good practice to use whenever you’re learning.

~& (sigpam) is used to print its argument every time that argument executes. So, if you wanted to see how many times your program executed foo, you would write foo bar. Then, when your program runs, it will print foo on a new line of output every time the program comes across it by recursion.

But there are more. Check out the aforementioned Troubleshooting page to see other handy debugging runes and how to use them.